- Products

- All Products

- RF PA Extension Kit

- Wireless Microphone Upgrade Packs

- In-Ear Monitor Upgrade Packs

- Wireless Microphone Antennas

- Wireless In-Ear Monitor Antennas

- Antenna Distribution for Microphones

- Antenna Combiners for In-Ear Monitors

- Multi-Zone Antenna Combiners

- Spectrum Tools

- Accessories, Cables and Parts

- Solutions by Venue

- Resources & Training

- Performance Tools

- About Us

December 15, 2014

James Stoffo In-Depth on the Groundbreaking VHF/UHF UV-1G Intercom, from Radio Active Designs

Written by: Alex Milne

By pure coincidence, this year’s RF Venue InfoComm booth was right next door to the youngest and most exciting company in the wireless audio industry: Radio Active Designs. Radio Active Designs (www.radioactiverf.com), or “RAD” for short, is set to release their professional com system, the UV-1G, in the next few months. This intercom will be disruptive, to say the least—and who better to tell us why than one of RAD's key players: James Stoffo.

RAD was founded more than a decade ago by three leading wireless audio experts—freelance wireless coordinator and guru James Stoffo (formerly of Professional Wireless Systems), Senior RF Designer Henry Cohen of CP Communications, and Geoff Shearing, President of Masque Sound.

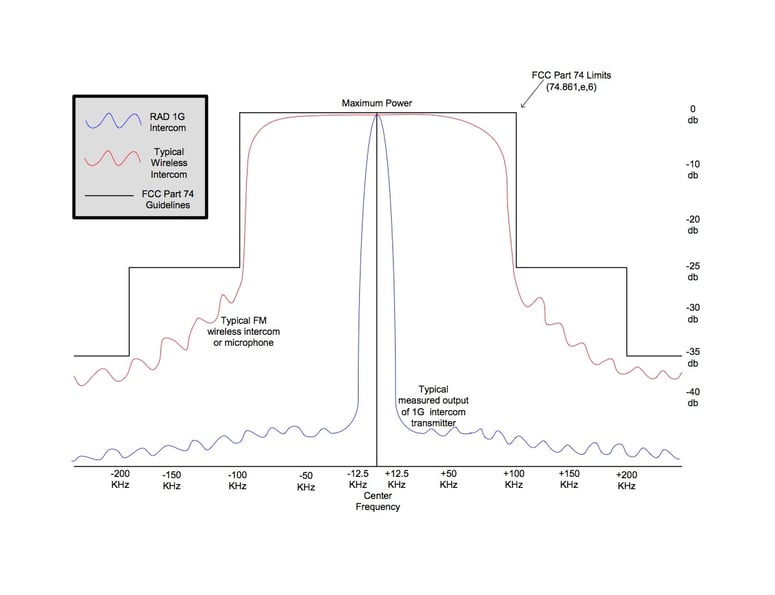

At InfcoComm, James and crew had a spectrum analyzer set up to visualize one of the UV-1G's big accomplishments—spectral efficiency. I watched an unrelenting stream of giddy techs and engineers gawk at the slim spectral footprint of the UV-1G compared to a standard 200 kHz wideband FM signal, then crane their necks in disbelief when told the UV-1G uses two radical and taboo wireless technologies: AM modulation and VHF transmission.

After the show, I wanted to get a more thorough understanding of what’s underneath the UV-1G’s hood, so I called up James for an interview. To his unending credit, I learned that he was talking to me while piloting a boat off the coast of Florida! Our skipper’s cap is off to you, James.

Give us the quick history on Radio Active Designs.

Henry and I have been working as coordinators and on large productions and events our whole careers, and Geoff has been involved with Broadway theater through his company, Masque Sound his whole life. Our other two partners, Jamie Schnakenberg and Mark Gubser, worked at Telex for a number of years so they’re also aware of all the interference issues, and of the issues surrounding white space devices, and spectral congestion.

We were walking around at NAB show in 2001 completely underwhelmed with all the other wireless intercom equipment out there. We didn’t see anybody looking at any of the potential issues with congestion, and so Geoff said, ‘hey, let’s write a spec to do this.’ It was a pie in the sky dream to start this new company and design something in VHF. And after that NAB show, more like 2003, Geoff approached me and said ‘let’s do this.’

James accepting the TVTechnology Superior Technology Award at NAB '13.

James accepting the TVTechnology Superior Technology Award at NAB '13.

So, we started looking at what we could do to improve this congestion. If you look at a typical show, most of the frequencies in use are wireless intercoms. If you have 100 wireless systems on a show, you know 24 might be in-ears, maybe 30 mics, but more like 60 or 70 coms. We knew if we came out with an intercom we would make the biggest impact on spectral congestion. That’s why we decided to go with a wireless intercom first. Coms outweigh everything else on the show.

Plus, we knew if somebody didn’t do something no one would be able to do these big shows anymore. In fact, we were just on a conference call today with the Chief Frequency Coordinator for the Super Bowl and the guys from ABC, NBC, and FOX—we’re still trying to figure out what to tell the FCC in terms of giving us some spectrum that we can continue to operate in.

The UV-1G does something interesting with duplex across both UFH and VHF, right? Could you explain that some more?

Whenever any of us work as coordinators at large events, the first thing that we do is write a radio spectrum band plan. And that would be: put your in-ear monitors in one band, and put your wireless microphones in a different band so you have better range and less noise and better audio, and put your intercoms here, and your IFBs here, and so forth.

When we designed the UV-1G we said, if we can come out with our own system, let’s put the receiver in a band where there is no possible way that any base station transmitter will ever create any splatter on to the receivers. So, by coming out with UHF base station transmitter, and a VHF pack receive, we completely control the band plan. There’s no way anybody is going to be able to come out now and put any base transmitters on top of the base receivers.

Also, if you look at the spectrum, since 1990, the radio spectrum has all moved up to UHF. It used to be all VHF. Now, VHF is pretty much wide open. We thought we could make the biggest impact on congestion if we put the packs in VHF. So, if you have a big show, like the Oscars or Grammys, with 120 intercoms packs, we pull those completely out of the UHF band and free up all of that spectrum so everyone with in-ears, mics, and base transmitters can now have 120 extra frequencies with the current FM technology on the market.

Plus, nobody even wants to make any mics down there [in VHF] because there’s this perception that the audio’s not as good. But for coms, it’s just fine. As a byproduct, we have a spectral band plan so we don’t create any interference in our own system.

I just want to get this straight. The belt packs are transmitting in VHF, and the base stations are transmitting in UHF?

That’s right.

VHF has a poor reputation, for a lot of reasons. Would you say some of them are unfounded?

When all of the founding members of RAD got into this business everything was VHF. There was no UHF equipment. Everything on every TV show, Broadway show, and movie back then was VHF—and no one had a problem with it.

There really is no difference in whether a system works in VHF or UHF. The only difference is the antenna has to be bigger in VHF. That was a big reason why all of these manufacturers went to UHF. There’s no other technical reason for why anyone would have to seek a different RF band.

We have all seen that band empty now for almost twenty years. Our joke at RAD is VHF is like that bar that used to be crowded, but now no one goes there anymore. There’s nothing wrong with the bar—it’s just that people have the perception that it was crowded, so they don’t go there anymore.

I’ve approached other major wireless manufacturers about this [manufacturing VHF equipment] long before the concept of RAD, and they said ‘well, we don’t want to go back to the long antennas.’ I said, well, ‘what about an internal antenna?’ They said ‘you have to patent that or get into licensing fees.’ So everybody was coming up with all these reasons for why not to go back to VHF.

So we said, 'alright, it’s our company, and we don’t want external antennas, what other types of antennas can we use?' We played around with a variety of internal VHF antennas before settling on our current version. By looking at one of our packs, you would never know it operates in VHF. It’s got the same range as UHF, it’s got the same audio as an FM system, but it’s in VHF, and we still have internal antennas.

Since we are the first to go to internal VHF antennas, I think you’re going to start seeing the other major wireless manufacturers start to come out with VHF. Someone had to be the first. That was us.

Can we talk about AM?

Sure.

Why did you choose to use AM (amplitude modulation) instead of the industry standard FM (frequency modulation).

Our primary goal for the UV-1G was to be spectrally efficient. So, we started to look at methods of modulation that were more spectrally efficient than the digital and the FM technology that are on the market now. AM, out of all these technologies, is the most spectrally efficient. The double sideband enhanced narrowband AM system that we deploy on our system is actually 12 times more efficient than a digital signal, and 12 times more efficient than an analog FM system.

So, the UV-1G is using an analog signal to be more spectrally efficient?

Yes, it’s an analog signal. A double sideband suppressed carrier amplitude modulated RF signal.

How is your double sideband AM different from the double sideband AM used in broadcast AM radio?

Well first off, we spent an awful lot of time and money in making the AM sound as good as an FM carrier. And the way we did that was by converting the analog audio into digital, then manipulating it digitally by compressing and pre-emphasizing with DSP. This proprietary DSP is why it sounds so good, and why it doesn’t sound like double sideband AM at all. It gets converted from analog to digital eight times from pack mic to pack base and back out to pack with less than 5 milliseconds of latency.

That’s really interesting. It’s like a mating of very old and very new technologies in the same device.

Oh yeah. If you pull all of the DSP out of the UV-1G, the analog stage of the technology is from 1920. Internal antennas, AM, VHF: this is all stuff that’s been around whenTesla was building radios. Really, all we did was bring it into the 21st century by converting it to digital and playing with the audio so it sounds as good as an FM system. The only other radios out there besides broadcast AM that use AM are aircraft.

My basic understanding of the merits of FM vs AM is that, generally, AM is more spectrally efficient, and FM generally has greater audio fidelity and also greater resistance to competing signals on the same frequency, greater resistance to interference. So how does the UV-1G deal with interference in ways that are different than an FM system would?

Well, we have tested the UV-1G on all of our shows. I’ve been to many shows with lots of lighting, like the Latin Billboards and Grammy’s, and put the packs up against these massive lighting walls to give them as much interference as I possibly can [LED lighting walls are notoriously strong emitters of interfering noise], and they were just impervious to interference from lighting walls and video walls and other things. A lot of that interference is in VHF, but our DSP does such a good job of cleaning it up you can’t tell it’s there.

There are still things we need to play with. We still have some field trials to do before we have an official product release, but we are confident the system will be extremely resilient on release.

You’ve been at this for a while, right?

Yes, the spec was written 13 years ago. We started R&D on a component level about ten years ago, and we’ve been at it for five years working out the bugs and details, and turning it from a thought into an actual product.

What were the biggest technological challenges you had to overcome along the way?

The biggest challenges were getting good range from these internal antennas, and getting the audio quality up to where we wanted it.

And now you’ve got them right.

Right. And in fact, this year’s InfoComm was the first time that Geoff, Henry and I looked at each other and said, ‘alright, now we’ve got a system.’

Tag(s):

Alex Milne

Alex Milne was Product Marketing Manager and Digital Marketing Manager for RF Venue, and a writer for the RF Venue Blog, from 2014-2017. He is founder and CEO of Terraband, Inc., a networking and ICT infrastructure company based in Brooklyn, NY., and blogs on spectrum management, and other topics where technology,...

More from the blog

Knowledge Guides

Another Look at RF for the Super Bowl

4 min read

| February 13, 2015

Read More

Knowledge Guides

Don't Overlook DECT: 1920-1930 MHz Microphones May Be Coming Soon to an Install near You

7 min read

| December 15, 2014

Read More

Knowledge Guides

RAD UV-1G Intercoms Land at Pro Bowl and Super Bowl

6 min read

| January 27, 2015

Read More

Subscribe to email updates

Stay up-to-date on what's happening at this blog and get additional content about the benefits of subscribing.