- Products

- All Products

- RF PA Extension Kit

- Wireless Microphone Upgrade Packs

- In-Ear Monitor Upgrade Packs

- Wireless Microphone Antennas

- Wireless In-Ear Monitor Antennas

- Antenna Distribution for Microphones

- Antenna Combiners for In-Ear Monitors

- Multi-Zone Antenna Combiners

- Spectrum Tools

- Accessories, Cables and Parts

- Solutions by Venue

- Resources & Training

- Performance Tools

- About Us

July 1, 2015

An In-Depth Look at Wireless Audio for The Public Theater’s Free Shakespeare in the Park

Written by: Alex Milne

This May, The Public Theater’s Free Shakespeare in the Park opened with a six week run of The Tempest, starring Sam Waterson and Jesse Tyler Ferguson, and continues July 23rd through August 23rd with Cymbeline, featuring Lily Rabe and Hamish Linklater.

Free Shakespeare in the Park, which has been produced since 1962 by The Public Theater, is a storied New York City tradition. It whips people into a frenzy; performances are known to create lines of air mattress toting Shakespeare fans up to a mile long.

Shakespeare in the Park is of interest not only for the caliber of talent and performance, but for the quality of its technical production, too.

The venue, Central Park’s 1,800 seat open-air Delacorte Theater, presents rare challenges to set designers, lighting, and audio engineers.

Outside the Delacorte Theater in the Shakespeare Garden. Photo courtesy Boris Dzhingarov.

Outside the Delacorte Theater in the Shakespeare Garden. Photo courtesy Boris Dzhingarov.

When it comes to wireless, the Delacorte is like the worst of both worlds. It frazzles designers with the complications of outdoor productions—wind, rain, excessive path-loss—but also with the insanely crowded urban spectrum found in Manhattan.

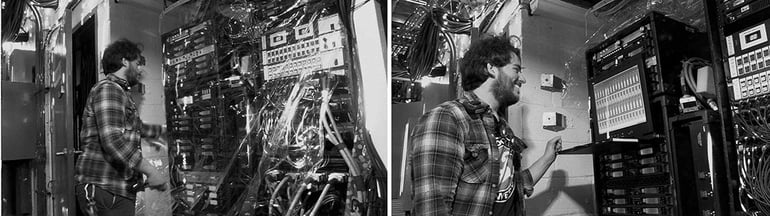

Matt Bell, Assistant Audio Supervisor at The Public Theater (who is standing beside one of the speakers for the production in the image that leads this article), said it best when he told me: “We essentially have to load an entire Broadway quality sound system into a natural park.”

This year, The Public made use of two RF Venue products—the Spotlight antenna and Optix fiber-optic remote antenna system—on The Tempest and Cymbeline, and Matt invited us to stop by for a closer look.

Matt holding one of two Spotlight antennas before installation.

Matt holding one of two Spotlight antennas before installation.

All of The Public’s wireless and sound reinforcement are provided by Masque Sound, whose unrivaled expertise in theatrical audio rental, support, and frequency coordination precedes them. Masque works with The Public on the initial build, but also provides support during the production if dropouts arise.

The Tempest and Cymbeline use up to 40 channels of Sennheiser 3532 and Sennheiser 2000 series, along with Shure IEMs, two matrixed intercom main-stations, and three Telex BTR–800s.

The racks are underneath transparent tarpaulin to keep out the rain.

Though wireless is of utmost importance, the unique, intimate nature of Cymbeline's set design paired with the Delacorte’s unconventional upstage area—an expanse of open water named Turtle Pond—makes minuscule wireless audio signals vanish into the trees.

“There is no bounce to the room or anything to reflect RF back onto our actors and antennas, like you would have in a traditional theater,” continues Bell. “We used two RF Spotlight’s to get our antennas physically closer to our actors. Since they’re low profile, we built them into our set pieces and under the deck, and our antennas are 120 feet closer than we would have otherwise been able to get them.”

The Spotlight’s thin 7mm disc allowed The Public Theater to mount both transmit and receive antennas for some of their UHF equipment directly underneath the actors, maximizing signal-to-noise ratio. They built two of them into the deck, splitting the center mark, with one stage left and one stage right.

The Spotlights are connected to the Optix converters, which, in Matt’s words, “let’s us get as close to the noise floor of the cable as possible.”

“The park is so big,” he continues, “and all of our cable runs are so long that we want to get things down to as little loss as possible, to get the signal stronger. The 2.5 dB loss of the Optix is a whole lot better than our 10–12 dB loss of coaxial cable.”

I asked Matt if he could provide us with RF scans of the spectrum during an actual performance to help visualize the benefits of the Spotlight, which is much easier to show than tell.

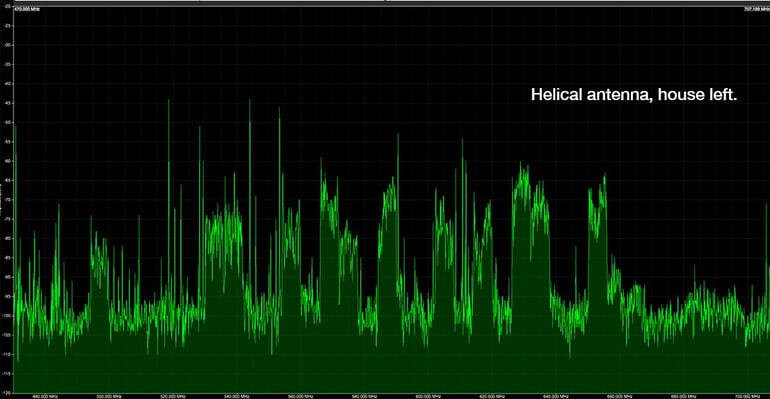

Above is a spectrum trace of the entire UHF broadcast band from the perspective of a PWS helical antenna mounted house left. That is, this scan was taken using a spectrum analyzer connected directly to the output of one of the helicals mounted in the audience, pointing at the stage. In previous years, Shakespeare in the Park designers used PWS helical antennas for the entire system, and I believe they still used them for some channels this year, in addition to two Spotlights.

Helicals create a narrow beam of coverage. They tend to dramatically increase the signal strength of signals located in front of the antenna element, while reducing the signal strength of “off-axis” signals on either side. That’s why we see such a heterogenous rendering of signal strengths in this scan. There are many TV stations that appear to be very, very loud. Those stations transmitters are probably on the horizon right where the helical is pointed. Others are less pronounced. These are probably off to the sides of the antenna.

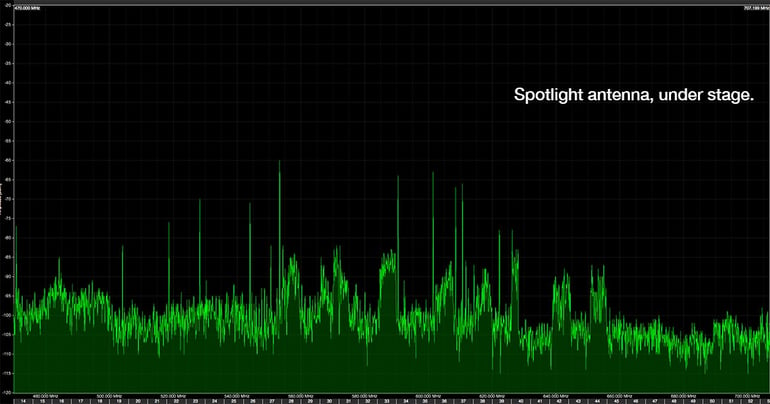

Now, let’s see a scan from the perspective of the Spotlight.

Most of the TV station signals that the helical picked up are significantly less powerful, and some of them have disappeared completely into the noise floor, while the mic and IEM signals (the tall, narrow spikes), the signals that we want, are the same amplitude, or even stronger than they were with the helical.

Since the coverage pattern of the Spotlight creates a “hemisphere” or “bubble” of reception above it and directly around it, while attenuating signals arriving from the far horizon (like the TV stations around Central Park), and because the sound design team has the Spotlight mounted directly underneath the stage below the performers, the signal-to-noise ratio is superb.

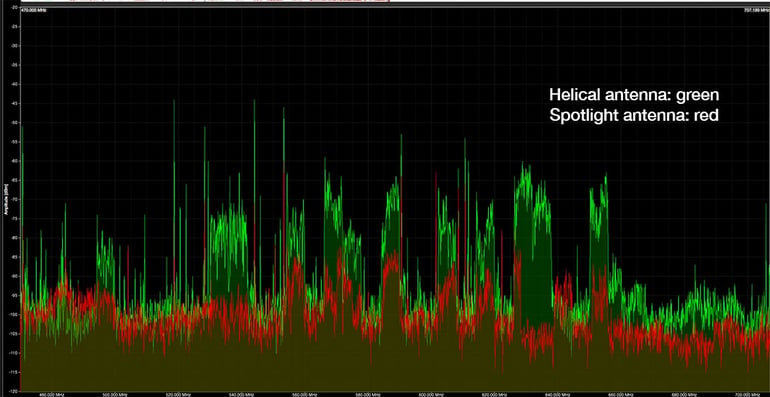

Here’s an overlay of the two scans for an even better visualization of just what a difference the Spotlight makes.

The point of juxtaposing these two scans is not to insinuate that there is something inferior about PWS helicals.

Antennas might be thought of as lenses. Lenses can have very different characteristics, long or short, etc, that are appropriate for different situations. You would not use a telephoto lens to take a panoramic photographic, or a wide angle lens to take a photograph of the moon.

The lens analogy is especially apt here because these scans are taken directly from the output of their two respective antennas, so the spectrum analyzer is looking through the antennas and seeing the spectrum from the perspective of the receivers, which is what really matters.

In this case, in Central Park, which has very crowded spectrum, the Spotlight antenna is a better choice for the application. Under different circumstances, a PWS helical or some other type might be a superior choice.

Production credits for Cymbeline include direction by Daniel Sullivan, scenic design by Riccardo Hernandez, costume design by David Zinn, lighting design by David Lander, sound design by Acme Sound Partners, hair and wig design by Charles G. LaPointe, and original music by Tom Kitt.

Alex Milne

Alex Milne was Product Marketing Manager and Digital Marketing Manager for RF Venue, and a writer for the RF Venue Blog, from 2014-2017. He is founder and CEO of Terraband, Inc., a networking and ICT infrastructure company based in Brooklyn, NY., and blogs on spectrum management, and other topics where technology,...

More from the blog

Knowledge Guides

International A/V Giant PRG Forgoes Coax in Favor of RF Optix RFoF System on Demanding New York City Corporate Event

4 min read

| December 15, 2014

Read More

RF Spotlight Antenna

RF Venue Co-Founder Robert Crowley Talks Product Design

10 min read

| May 31, 2015

Read More

Knowledge Guides

Reduce, Reuse, Rejoice: The Magic of Frequency Reuse

11 min read

| December 15, 2014

Read More

Subscribe to email updates

Stay up-to-date on what's happening at this blog and get additional content about the benefits of subscribing.